Fear of Holes (With Due Apologies to Jacob Geller)

My dad is a fan of horror movies. From the cerebral horror of something like The VVitch to low-budget trash like Mourning Wood or Zombeavers (which he insists is the Citizen Kane of Zombie Beaver movies), he’ll watch it all, and if you ask him if it was good, he’ll say “I enjoyed it.” There is, to my knowledge, one exception: he has never finished The Descent. He didn’t even get to the part where the monsters started showing up. The simple tightness and total darkness freaked him out enough to stop.

I am not the first person to point out that caves are spooky. In the video that inspired this essay, Jacob Geller did just that. So when our fearless thought-leader Prismatic Wasteland decided that the next Blog Bandwagon was going to be about holes, I knew where my clout-chasing would lead me. So let’s talk about holes, the underground, and just why they can be so fucking scary, and maybe learn something about how that can be used in games.

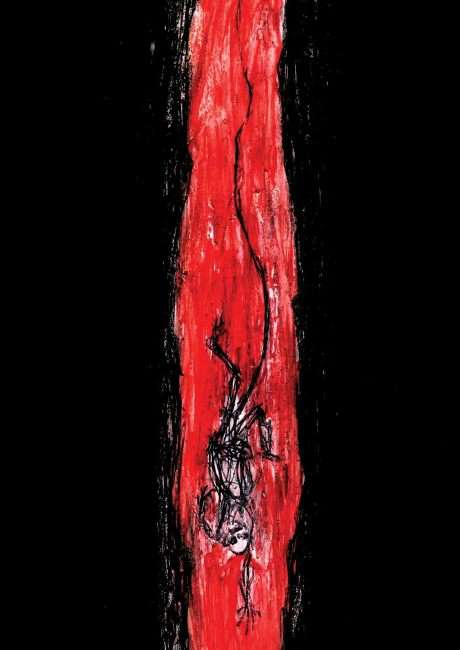

|

| Hope you prepared Feather Fall |

My first ever encounter with caves in fiction was probably This Dark Endeavour: The Apprenticeship of Victor Frankenstein. A supposed origin story to why Victor got so into weird alchemical shit in the first place, it centers around him trying to halt the disease of his twin brother Konrad, and the weird love triangle they have with their cousin Elizabeth. The thing I remember the most is the second ingredient they need for their elixir, part of a coelacanth which turns into some kind of boss fight, but the relevant part here comes before that. On their way to the underground lake where the coelacanth resides, their passage narrows down to a tight hole. Konrad goes first, and then Victor follows because if one twin can fit then so can the other, right? Except Konrad had been wasting away in bed for months.

Victor is stuck.

And that gets to the fundamental terror and claustrophobia of holes in the earth: they are inviting, soliciting passage forward, but they are also greedy things, which often choose not to let go. He makes it out of course, he’s destined to die in the Arctic chasing down his creation, but that is simply because in a lot of ways the earth let him go, provided a way for him to twist his body to escape. When one is stuck, after all, they cannot be cut out, for risk of swallowing up more people beneath the stone.

|

| I mostly bought it because of the cover |

Junji Ito’s The Enigma of Amigara Fault makes this open invitation to die explicit: the holes that are exposed following an earthquake are shaped like people, waiting to be claimed. It is at once about that urge everyone has to jump when looking over a great height, but also the feeling of being trapped. Because people find that there are holes which have their shape. And in they go, because they have to accept that invitation. This of course is where the famous meme comes from, but to my mind the most fascinating part of the holes is their shape, such that one can always go forward but never back. That and, of course, the nightmare our protagonist has, about a man trapped by a deformation behind hundreds of meters of darkness, screaming out for help, with no one able to come find them.

The Zothique stories of Clark Ashton Smith are a mixed bag, insofar as I’ve read them (and some of the good ones are tainted by Smith’s antisemitism), but the sorcery at the end of the earth is a rich ground for the imagination. While my personal favorites are probably Xeethra (where a boy ventures into the underworld and discovers his past life) and The Master of the Crabs (take a goddamn guess), today I want to talk about The Weaver in the Vault. In it, a trio of mercenaries are hired to retrieve a relic from a tomb for the queen. They arrive at the tomb and find it empty. The bodies are gone. As they venture further, they are undone not by blade or spell, but by an earthquake, implied to be a punishment upon the kingdom for their sins. Two of the men die right away, but the last one lingers, and gets to see the titular Weaver, an orb of light, which feeds upon the dead. Ultimately, it's not an antagonist, not a predator, simply a scavenger, claiming scraps of what belongs to the earth. It is, like many of the Zothique stories, simply a tale of something terrible happening to someone for no good goddamn reason at all.

|

| I did not buy this one because of the cover |

That arbitrariness can also be found in the many real-life experiences of delving into holes. From famous stories like Floyd Collins or the Tham Luang cave rescue to less famous ones like the death of John Edward Jones, people die in caves. Our biology is simply not built to understand them, to survive in them. Yet like those who entered Amigara Fault, we are compelled to. I watch caving content, and especially cave diving content, because it makes my body scream. That fear of being trapped is a visceral thing, but people keep doing it. I’m not brave enough, so I try to keep a distance. And what better distance is there than pretending to explore a cave while being an elf?

|

| A diagram of John Edward Jones' final resting place. All they could do was sedate him. |

Growing up, I was The Tabletop Gamer of my friend group, which meant that a lot of my thinking about roleplaying games had to be done from a combination of first principles, the Kobold Guide to Game Design (not to brag but my copy is autographed), and the help of the fine folks at the Paizo forums. One thread, about advice for delving dungeons, has stuck with me. Paraphrased, “When given a choice between going up and going down, always go up first. Up is finite, down…less so.” This kind of thing is obvious in most OSR spaces (heck, Gary Gygax recommends in ODND to start by drawing half a dozen levels of underworld), but it blew my tiny little mind.

When I read the introduction to Frog God Games’ Cyclopean Deeps, I couldn’t just say “Oh, it’s an OSR-esque underdark hexcrawl, but kinda weirdly in Pathfinder for marketing reasons.” It advertised itself as being below the below, a land of strangeness and danger. It’s not, not really. It has dark stalkers, and duergar, and a cult civil war and stuff, but I didn’t know any better and frankly I didn’t understand it. But it was awesome. I felt the same way reading The Inner Sea World Guide, and its section on the non-copyright-infringing Darklands. To me, the interesting bits were the deepest, the Vaults of Orv, which could hold, well…anything. A Hollow-Earth style land of ziggurats and jungles and dinosaurs, mountains under hungry moons, and a massive darkened sea containing the last empire of the aboleths.

Wolfgang Baur (I assume? The essay isn’t credited but his name is on the book) wrote about the Underdark for Kobold Press, in what was probably my introduction to the topic. In his essay, he discussed the Underdark as a combination of the underworld and the most hostile wilderness imaginable. “Some players expect a sort of mega-dungeon. That’s the wrong way to look at it, in my opinion. It’s a wilderness without rest, without rules, without margin for a lot of error.” He brings up the greed of the earth, discussing how one can literally seal the exit behind the party and force them to contend with just how far they are from home. This approach, which didn’t really suit the 3.X era, later found its paragon in Veins of the Earth.

Veins of the Earth is a Lamentations of the Flame Princess supplement that thankfully can be used with other games without much trouble. Inspired by the fact that most caves in gaming functioned as little more than the mega-dungeons that Baur described, Patrick Stuart was inspired largely by actual caving, and it shows. Veins’ caves are the stuff of nightmares, often accessible only through crawling or death-defying climbs. Darkness is the default, a constant cloying thing that fucking hates you and necessitates pages on pages of lanterns to try and counter it. Perhaps the biggest thing it does is bring back the strangeness of the underworld, with a host of new monsters and by bringing back those kinds of consequences that Baur talked about. I’ve never played using the rules in Veins, and probably won’t get to, because I’ve slowly realized I’m not an OSR guy, but I will always love it for systematizing the kind of terror that made my dad stop watching The Descent.

People are not meant to go into caves. But we do so anyway, because of a human drive to go forward, explore frontiers, and all of that. Fortunately, modern caving (and especially cave diving) have come a long way from the days when Just Some Guy would go into a cave and starve to death. But it’s still fun to pretend, in the same way that roleplaying games have always let one engage with fictional scenarios they'd rather not get into in real life. And hey, in a roleplaying game, those holes really are made just for you.

Comments

Post a Comment